DIE VOLKSKUNSTSAMMLUNG VON MÜNTER UND KANDINSKY UND DER ALMANACH »DER BLAUE REITER<<

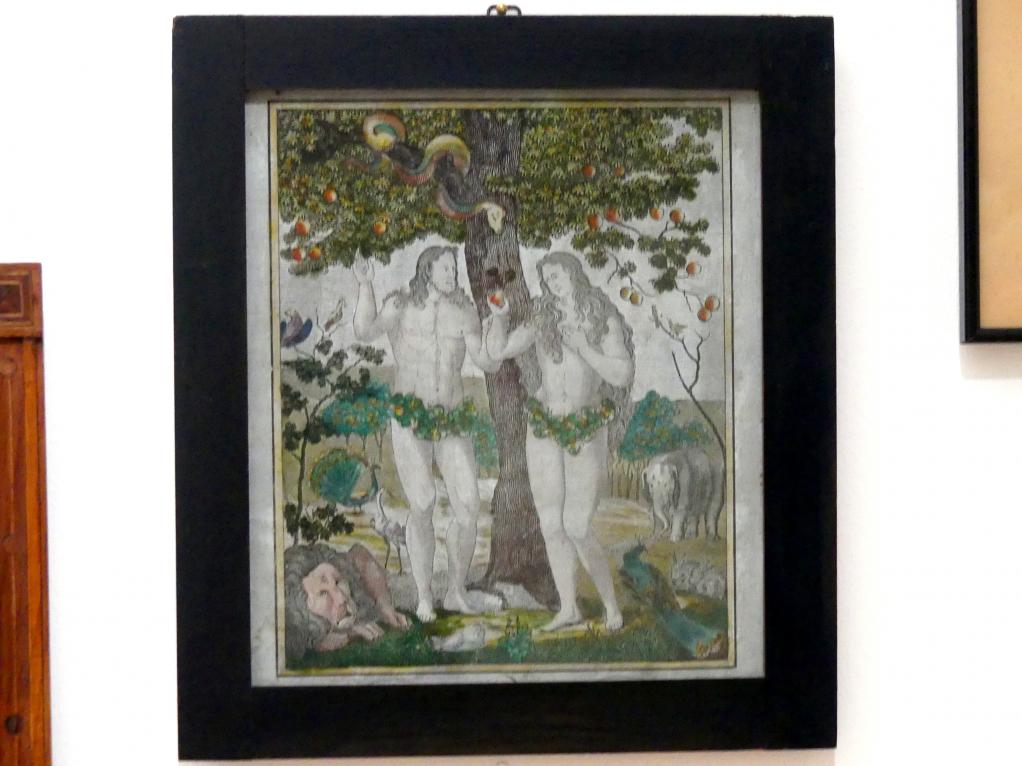

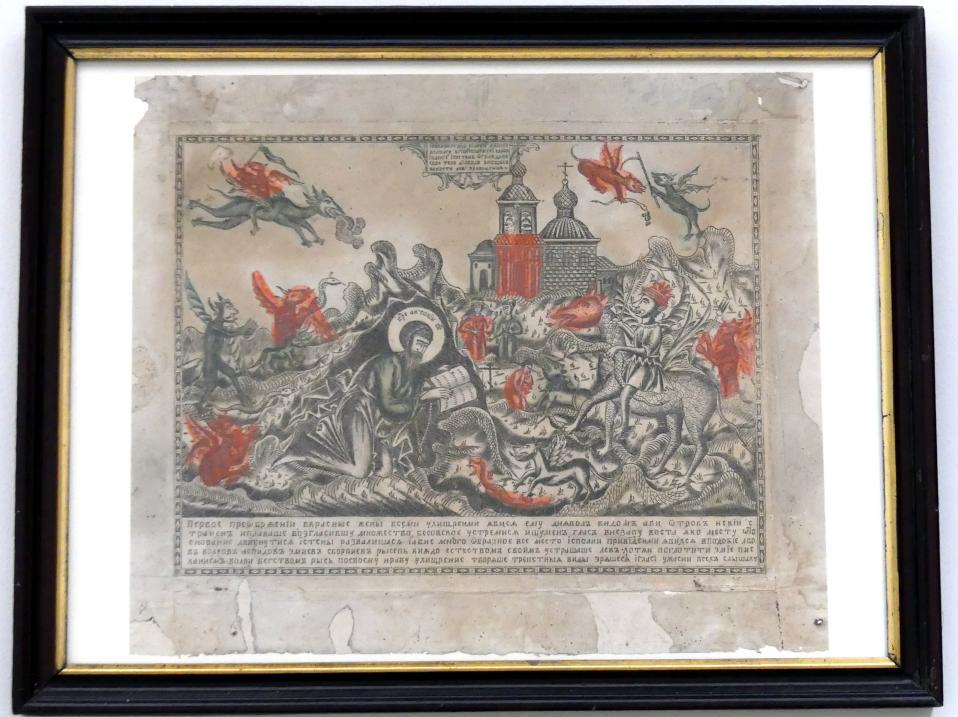

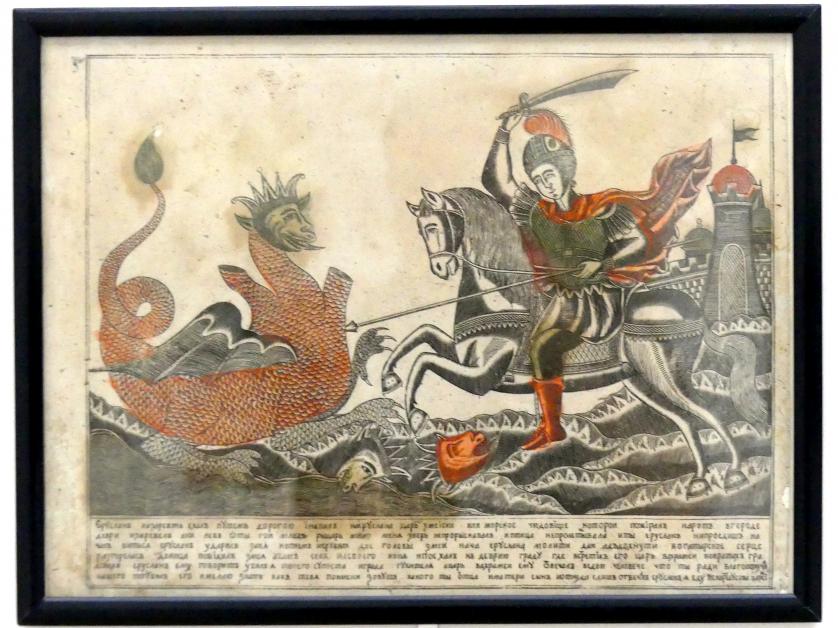

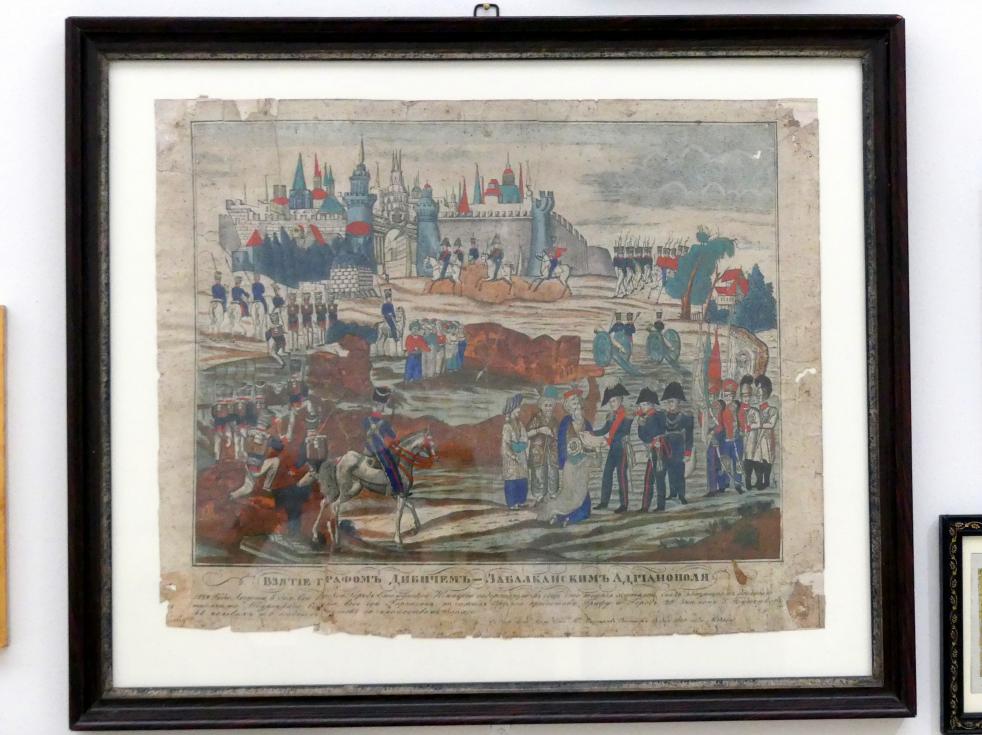

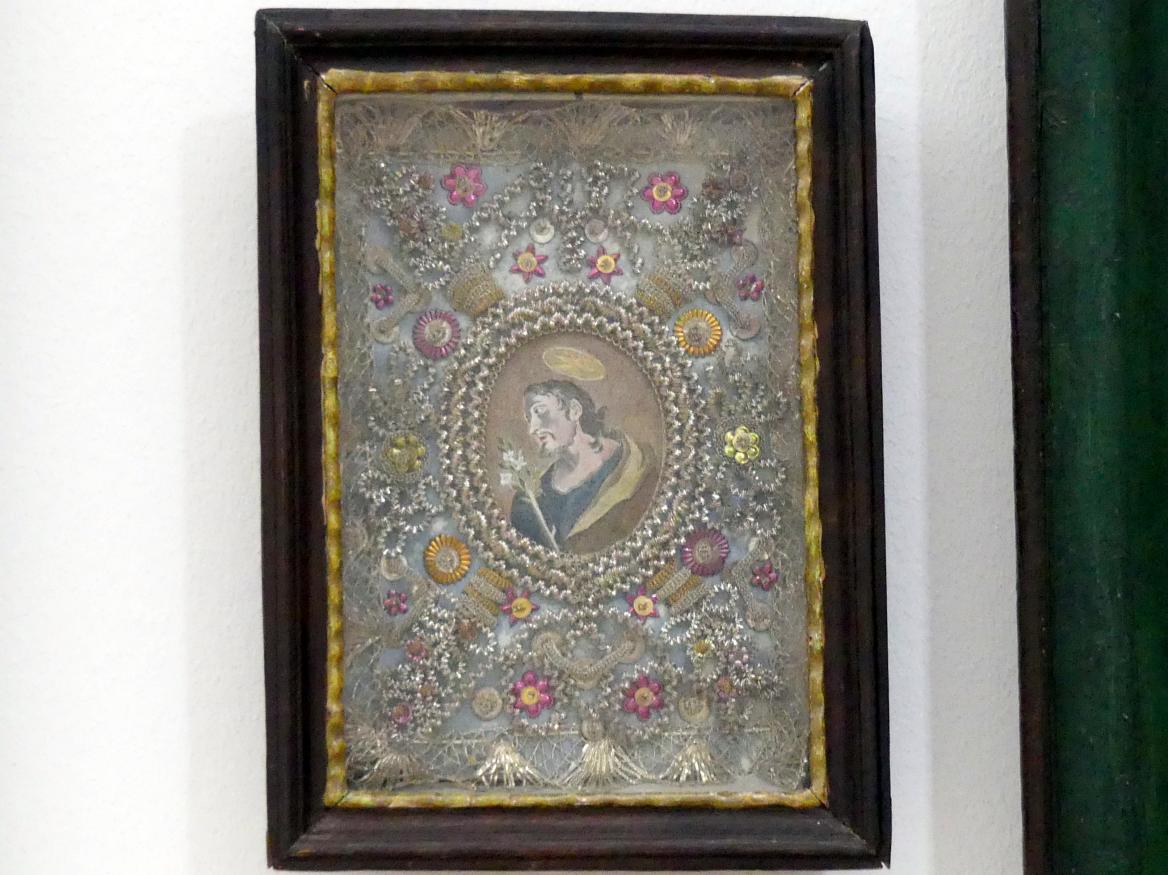

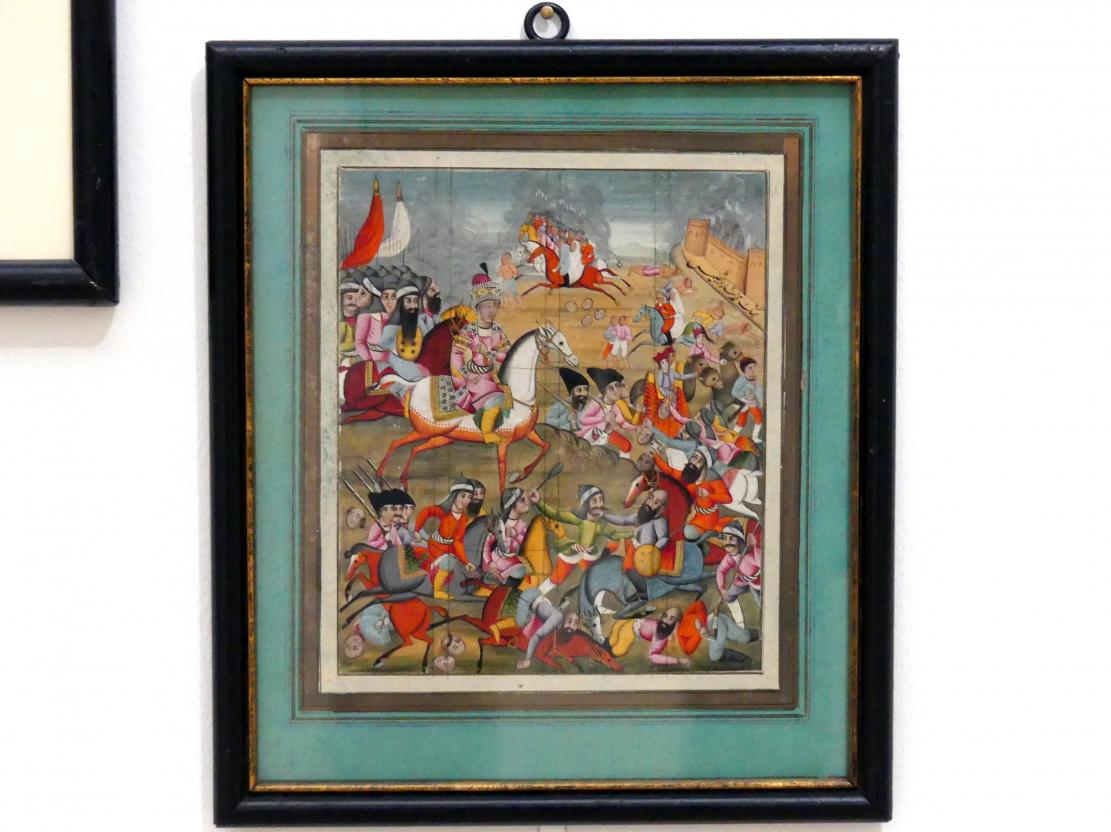

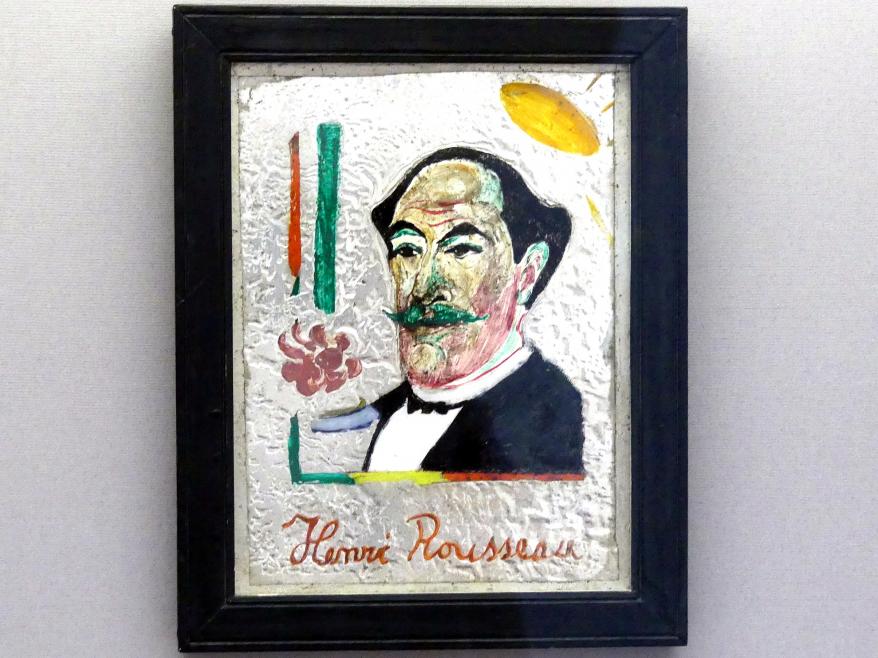

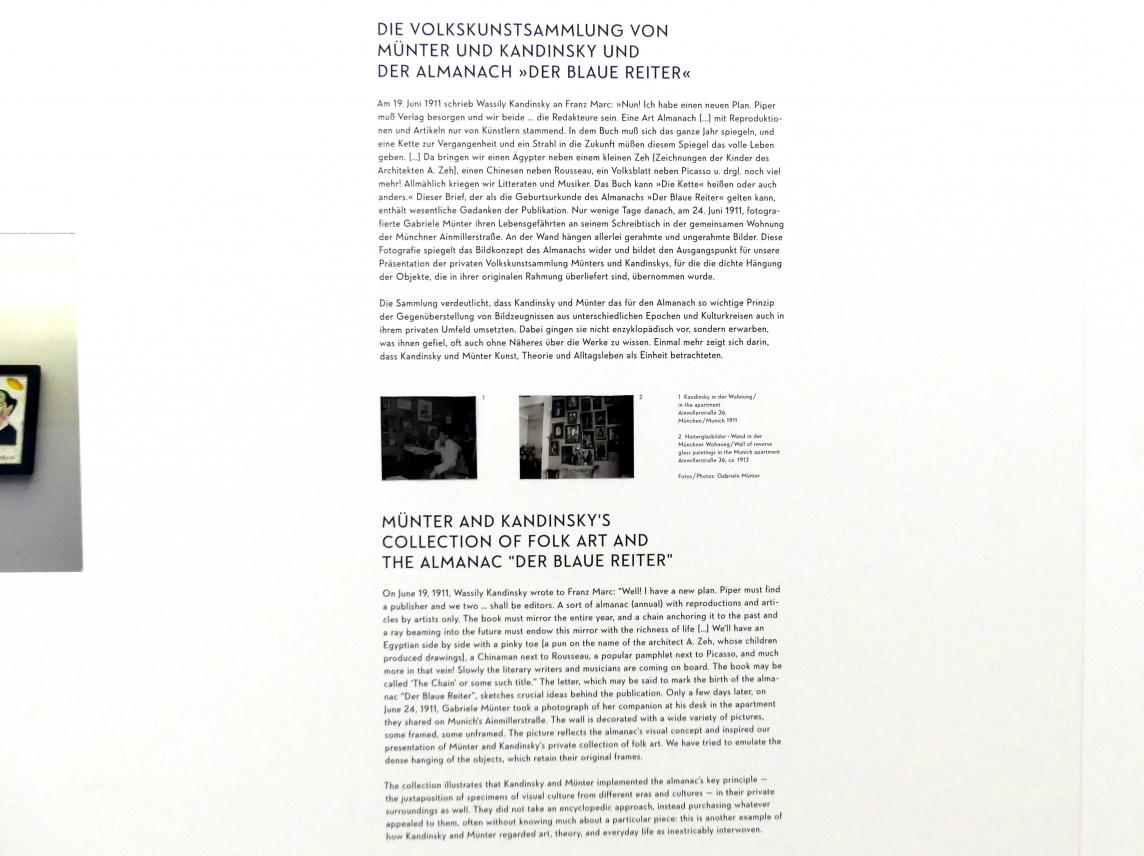

Am 19. Juni 1911 schrieb Wassily Kandinsky an Franz Marc: »Nun! Ich habe einen neuen Plan. Piper muß Verlag besorgen und wir beide... die Redakteure sein. Eine Art Almanach L. mit Reproduktionen und Artikeln nur von Künstlern stammend. In dem Buch muß sich das ganze Jahr spiegeln, und eine Kette zur Vergangenheit und ein Strahl in die Zukunft müßen diesem Spiegel das volle Leben geben. I. Da bringen wir einen Ägypter neben einem kleinen Zeh [Zeichnungen der Kinder des Architekten A. Zehl, einen Chinesen neben Rousseau, ein Volksblatt neben Picasso u. drgl, noch viel mehr! Allmählich kriegen wir Litteraten und Musiker. Das Buch kann »Die Ketten heißen oder auch anders. Dieser Brief, der als die Geburtsurkunde des Almanachs »Der Blaue Reiters gelten kann, enthält wesentliche Gedanken der Publikation. Nur wenige Tage danach, am 24. Juni 1911, fotografierte Gabriele Münter ihren Lebensgefährten an seinem Schreibtisch in der gemeinsamen Wohnung der Münchner Ainmillerstraße. An der Wand hängen allerlei gerahmte und ungerahmte Bilder. Diese Fotografie spiegelt das Bildkonzept des Almanachs wider und bildet den Ausgangspunkt für unsere Präsentation der privaten Volkskunstsammlung Münters und Kandinskys, für die die dichte Hängung der Objekte, die in ihrer originalen Rahmung überliefert sind, übernommen wurde.

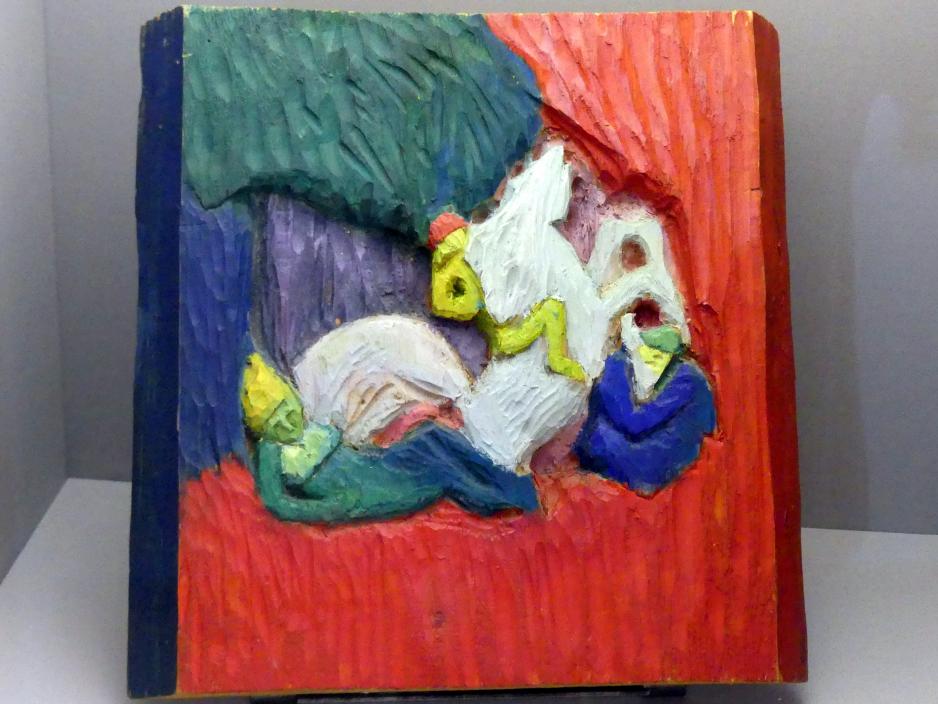

Die Sammlung verdeutlicht, dass Kandinsky und Münter das für den Almanach so wichtige Prinzip der Gegenüberstellung von Bildzeugnissen aus unterschiedlichen Epochen und Kulturkreisen auch in ihrem privaten Umfeld umsetzten. Dabei gingen sie nicht enzyklopädisch vor, sondern erwarben, was ihnen gefiel, oft auch ohne Näheres über die Werke zu wissen. Einmal mehr zeigt sich darin, dass Kandinsky und Münter Kunst, Theorie und Alltagsleben als Einheit betrachteten.

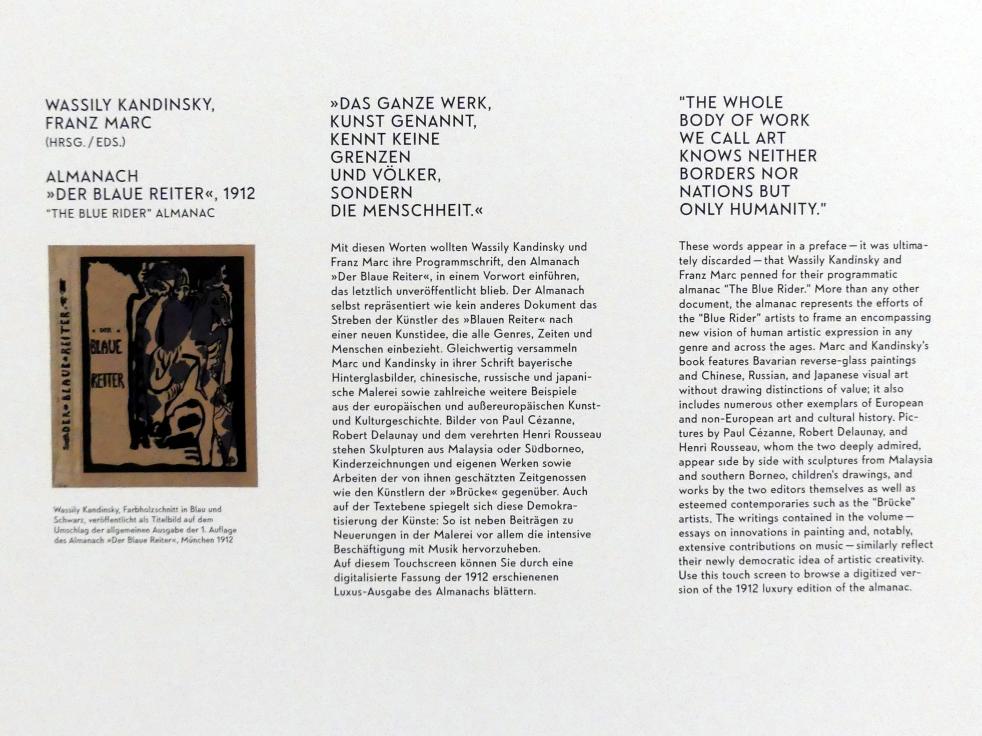

>>DAS GANZE WERK, KUNST GENANNT, KENNT KEINE SONDERN GRENZEN UND VÖLKER, DIE MENSCHHEIT.<<

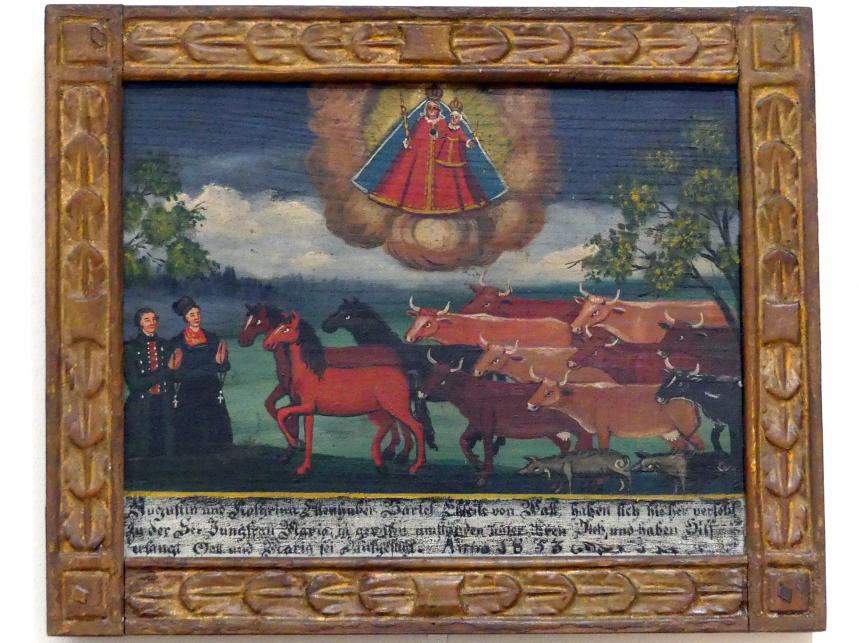

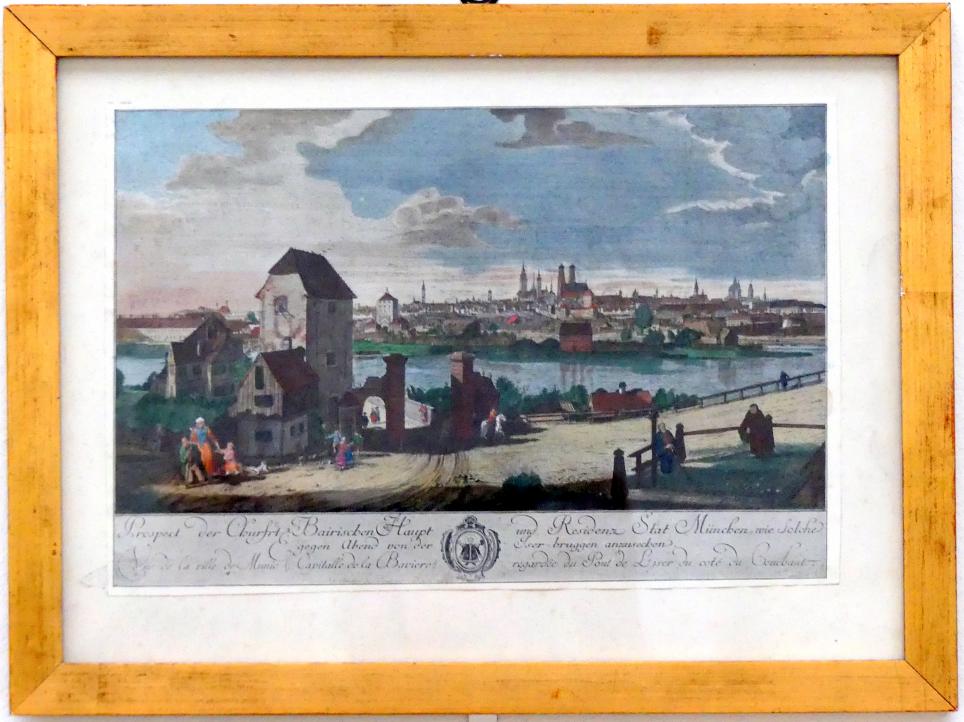

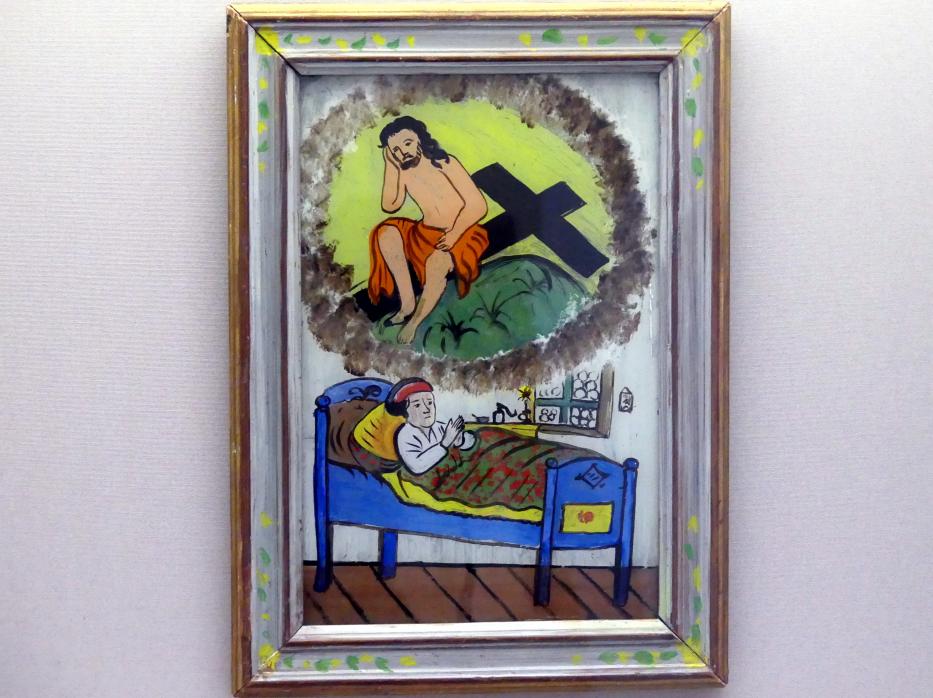

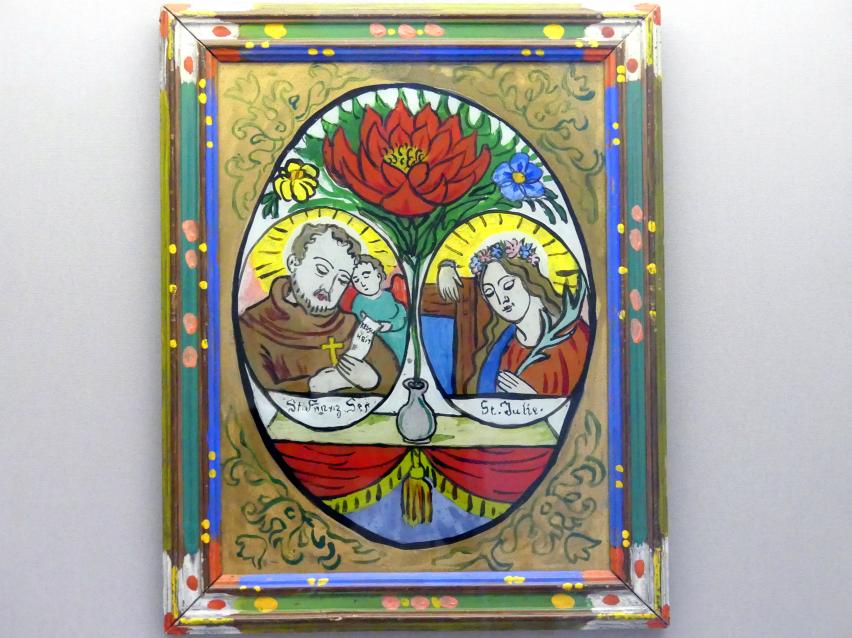

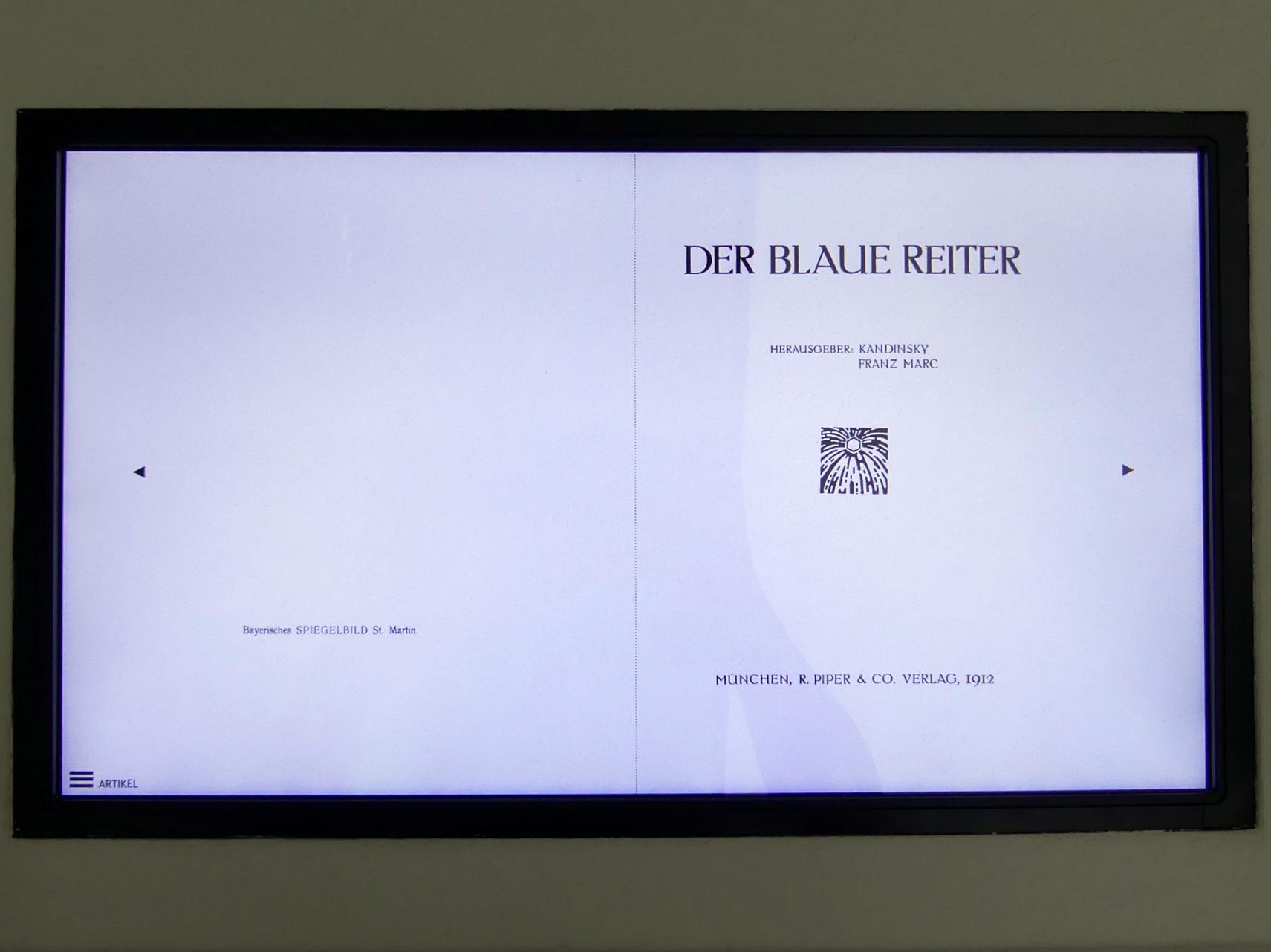

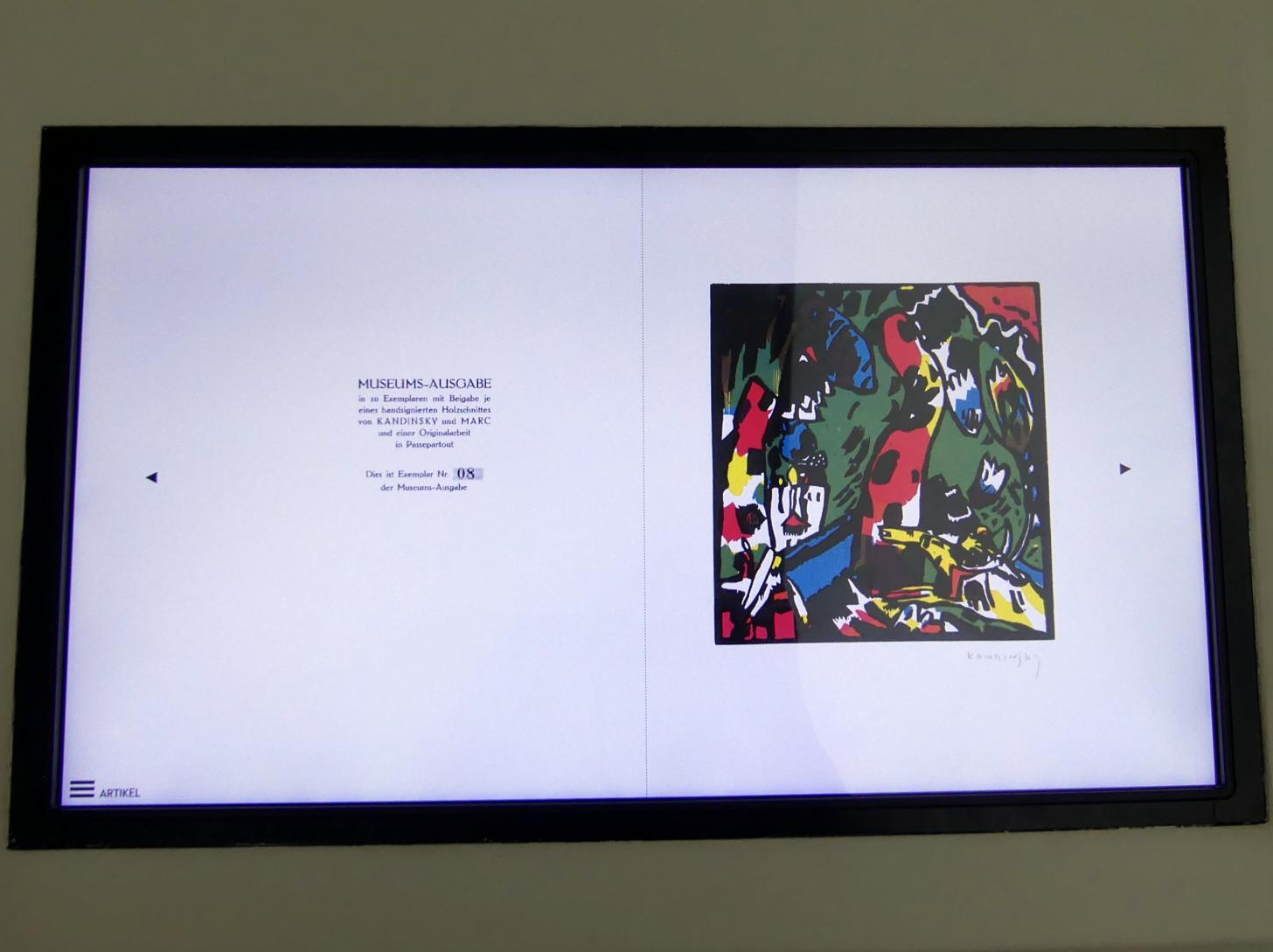

Mit diesen Worten wollten Wassily Kandinsky und Franz Marc ihre Programmschrift, den Almanach >>Der Blaue Reiter<<, in einem Vorwort einführen, das letztlich unveröffentlicht blieb. Der Almanach selbst repräsentiert wie kein anderes Dokument das Streben der Künstler des >>Blauen Reiter<< nach einer neuen Kunstidee, die alle Genres, Zeiten und Menschen einbezieht. Gleichwertig versammeln Marc und Kandinsky in ihrer Schrift bayerische Hinterglasbilder, chinesische, russische und japanische Malerei sowie zahlreiche weitere Beispiele aus der europäischen und außereuropäischen Kunst und Kulturgeschichte. Bilder von Paul Cézanne, Robert Delaunay und dem verehrten Henri Rousseau stehen Skulpturen aus Malaysia oder Südborneo, Kinderzeichnungen und eigenen Werken sowie Arbeiten der von ihnen geschätzten Zeitgenossen wie den Künstlern der »Brücke« gegenüber. Auch auf der Textebene spiegelt sich diese Demokratisierung der Künste: So ist neben Beiträgen zu Neuerungen in der Malerei vor allem die intensive Beschäftigung mit Musik hervorzuheben. Auf diesem Touchscreen können Sie durch eine digitalisierte Fassung der 1912 erschienenen Luxus-Ausgabe des Almanachs blättern.

DIE VOLKSKUNSTSAMMLUNG VON MÜNTER UND KANDINSKY UND DER ALMANACH »DER BLAUE REITER«

Am 19. Juni 1911 schrieb Wassily Kandinsky an Franz Marc: »Nun! Ich habe einen neuen Plan. Piper muß Verlag besorgen und wir beide... die Redakteure sein. Eine Art Almanach [...] mit Reproduktionen und Artikeln nur von Künstlern stammend. In dem Buch muß sich das ganze Jahr spiegeln, und eine Kette zur Vergangenheit und ein Strahl in die Zukunft müßen diesem Spiegel das volle Leben geben. [...] Da bringen wir einen Ägypter neben einem kleinen Zeh [Zeichnungen der Kinder des Architekten A. Zeh], einen Chinesen neben Rousseau, ein Volksblatt neben Picasso u. drgl. noch viel mehr! Allmählich kriegen wir Litteraten und Musiker. Das Buch kann »>Die Kette<< heißen oder auch anders.<< Dieser Brief, der als die Geburtsurkunde des Almanachs »Der Blaue Reiter<< gelten kann, enthält wesentliche Gedanken der Publikation. Nur wenige Tage danach, am 24. Juni 1911, fotografierte Gabriele Münter ihren Lebensgefährten an seinem Schreibtisch in der gemeinsamen Wohnung der Münchner Ainmillerstraße. An der Wand hängen allerlei gerahmte und ungerahmte Bilder. Diese Fotografie spiegelt das Bildkonzept des Almanachs wider und bildet den Ausgangspunkt für unsere Präsentation der privaten Volkskunstsammlung Münters und Kandinskys, für die die dichte Hängung der Objekte, die in ihrer originalen Rahmung überliefert sind, übernommen wurde.

Die Sammlung verdeutlicht, dass Kandinsky und Münter das für den Almanach so wichtige Prinzip der Gegenüberstellung von Bildzeugnissen aus unterschiedlichen Epochen und Kulturkreisen auch in ihrem privaten Umfeld umsetzten. Dabei gingen sie nicht enzyklopädisch vor, sondern erwarben, was ihnen gefiel, oft auch ohne Näheres über die Werke zu wissen. Einmal mehr zeigt sich darin, dass Kandinsky und Münter Kunst, Theorie und Alltagsleben als Einheit betrachteten.

MÜNTER AND KANDINSKY'S COLLECTION OF FOLK ART AND THE ALMANAC "DER BLAUE REITER"

On June 19, 1911, Wassily Kandinsky wrote to Franz Marc: "Well! I have a new plan. Piper must find a publisher and we two shall be editors. A sort of almanac (annual) with reproductions and arti cles by artists only. The book must mirror the entire year, and a chain anchoring it to the past and a ray beaming into the future must endow this mirror with the richness of life I. We'll have and Egyptian side by side with a pinky toe [a pun on the name of the architect A. Zeh, whose children produced drawings)], a Chinaman next to Rousseau, a popular pamphlet next to Picasso, and much more in that vein! Slowly the literary writers and musicians are coming on board. The book may be called 'The Chain or some such title." The letter, which may be said to mark the birth of the almanac "Der Blaue Reiter", sketches crucial ideas behind the publication. Only a few days later, on June 24, 1911, Gabriele Münter took a photograph of her companion at his desk in the apartment. they shared on Munich's Ainmillerstraße. The wall is decorated with a wide variety of pictures, some framed, some unframed. The picture reflects the almanac's visual concept and inspired our presentation of Münter and Kandinsky's private collection of folk art. We have tried to emulate the dense hanging of the objects, which retain their original frames.

The collection illustrates that Kandinsky and Münter implemented the almanac's key principle the juxtaposition of specimens of visual culture from different eras and cultures in their private surroundings as well. They did not take an encyclopedic approach, instead purchasing whatever appealed to them, often without knowing much about a particular piece this is another example of how Kandinsky and Munter regarded art, theory, and everyday life as inextricably interwoven.

"THE WHOLE BODY OF WORK WE CALL ART KNOWS NEITHER BORDERS NOR NATIONS BUT ONLY HUMANITY."

These words appear in a preface- it was ultimately discarded-that Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc penned for their programmatic almanac "The Blue Rider." More than any other document, the almanac represents the efforts of the "Blue Rider" artists to frame an encompassing new vision of human artistic expression in any genre and across the ages. Marc and Kandinsky's book features Bavarian reverse-glass paintings and Chinese, Russian, and Japanese visual art without drawing distinctions of value; it also includes numerous other exemplars of European and non-European art and cultural history. Pictures by Paul Cézanne, Robert Delaunay, and Henri Rousseau, whom the two deeply admired. appear side by side with sculptures from Malaysia and southern Borneo, children's drawings, and works by the two editors themselves as well as esteemed contemporaries such as the "Brücke" artists. The writings contained in the volume essays on innovations in painting and, notably, extensive contributions on music-similarly reflect their newly democratic idea of artistic creativity. Use this touch screen to browse a digitized version of the 1912 luxury edition of the almanac.

MÜNTER AND KANDINSKY'S COLLECTION OF FOLK ART AND THE ALMANAC "DER BLAUE REITER"

On June 19, 1911, Wassily Kandinsky wrote to Franz Marc: "Well! I have a new plan. Piper must find a publisher and we two... shall be editors. A sort of almanac (annual) with reproductions and articles by artists only. The book must mirror the entire year, and a chain anchoring it to the past and a ray beaming into the future must endow this mirror with the richness of life [...] We'll have an Egyptian side by side with a pinky toe [a pun on the name of the architect A. Zeh, whose children produced drawings], a Chinaman next to Rousseau, a popular pamphlet next to Picasso, and much more in that vein! Slowly the literary writers and musicians are coming on board. The book may be called 'The Chain' or some such title." The letter, which may be said to mark the birth of the almanac "Der Blaue Reiter", sketches crucial ideas behind the publication. Only a few days later, on June 24, 1911, Gabriele Münter took a photograph of her companion at his desk in the apartment they shared on Munich's Ainmillerstraße. The wall is decorated with a wide variety of pictures, some framed, some unframed. The picture reflects the almanac's visual concept and inspired our presentation of Münter and Kandinsky's private collection of folk art. We have tried to emulate the dense hanging of the objects, which retain their original frames.

The collection illustrates that Kandinsky and Münter implemented the almanac's key principle - the juxtaposition of specimens of visual culture from different eras and cultures in their private surroundings as well. They did not take an encyclopedic approach, instead purchasing whatever appealed to them, often without knowing much about a particular piece: this is another example of how Kandinsky and Münter regarded art, theory, and everyday life as inextricably interwoven.