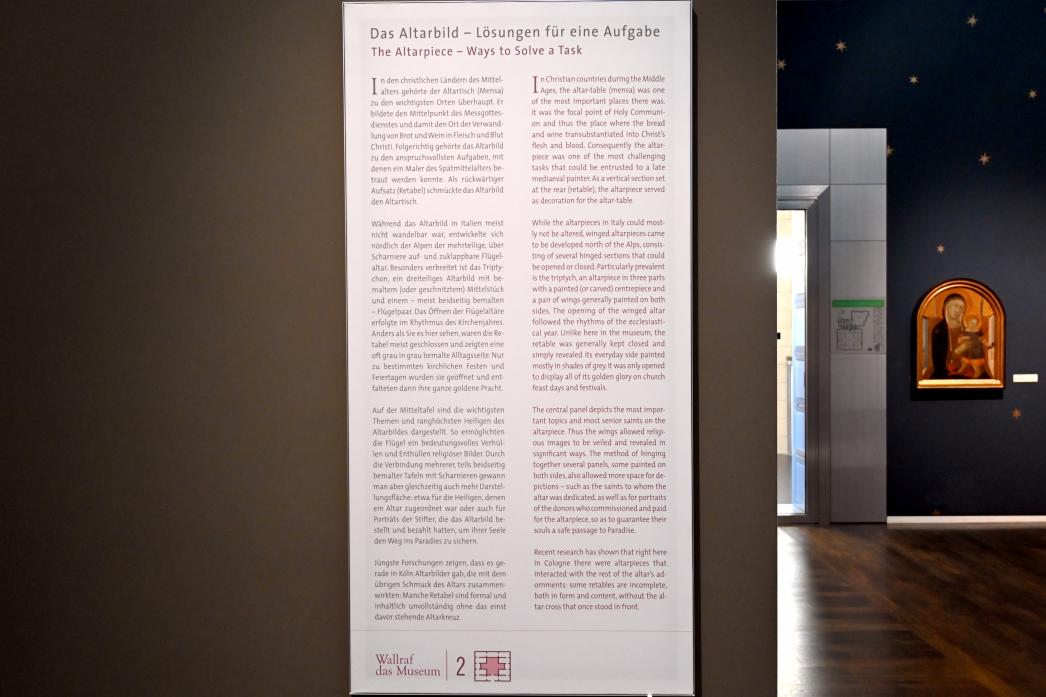

Das Altarbild - Lösungen für eine Aufgabe

In den christlichen Ländern des Mittelalters gehörte der Altarisch (Mensa) zu den wichtigsten Orten überhaupt. Er bildete den Mittelpunkt des Messgottesdienstes und damit den Ort der Verwandlung von Bout und Wein in Fleisch und Blut Christi. Folgerichtig gehörte das Altarbild zu den anspruchsvollsten Aufgaben, mit denen ein Maler des Spätmittelalters betraut werden konnte. Als rückwärtiger Aufsatz (Retabel) schmückte das Altarbild den Altartisch.

Während das Altarbild in Italien meist nicht wandelbar war, entwickelte sich nördlich der Alpen der mehrteilige, über Scharniere auf und zuklappbare Flügelaltar. Besonders verbreitet ist das Triptychon, ein dreiteiliges Altarbild mit bemaltem (oder geschnitztem) Mittelstück und einem - meist beidseitig bemalten - Flügelpaar. Das Öffnen der Flügelaltäre erfolgte im Rhythmus des Kirchenjahres. Anders als Sie es hier sehen, waren die Retabel meist geschlossen und zeigten eine oft grau in grau bemalte Alltagsseite. Nur zu bestimmten kirchlichen Festen und Feiertagen wurden sie geöffnet und entfalteten dann ihre ganze goldene Pracht.

Auf der Mitteltafel sind die wichtigsten Themen und ranghöchsten Heiligen des Altarbildes dargestellt. So ermöglichten die Flügel ein bedeutungsvolles Verhüllen und Enthüllen religiöser Bilder. Durch die Verbindung mehrerer, teils beidseitig bemalter Tafeln mit Scharnieren gewann man aber gleichzeitig auch mehr Darstellungsfläche: etwa für die Heiligen, denen ein Altar zugeordnet war oder auch für Porträts der Stifter, die das Altarbild bestellt und bezahlt hatten, um ihrer Seele den Weg ins Paradies zu sichern.

Jüngste Forschungen zeigen, dass es gerade in Köln Altarbilder gab, die mit dem übrigen Schmuck des Altars zusammenwirkten: Manche Retabel sind formal und inhaltlich unvollständig ohne das einst davor stehende Altarkreuz.

The Altarpiece - Ways to Solve a Task

In Christian countries during the Middle Ages, the altar table (mensa) was one of the most important places there was. It was the focal point of Holy Communion and thus the place where the bread and wine transubstantiated into Christ's flesh and blood. Consequently the altarpiece was one of the most challenging tasks that could be entrusted to a late mediaeval painter. As a vertical section set at the rear (retable), the altarpiece served as decoration for the altar-table.

While the altarpieces in Italy could mostly not be altered, winged altarpieces came to be developed north of the Alps, consisting of several hinged sections that could be opened or closed. Particularly prevalent is the triptych, an altarpiece in three parts with a painted (or carved) centrepiece and a pair of wings generally painted on both sides. The opening of the winged altar followed the rhythms of the ecclesiastical year. Unlike here in the museum, the retable was generally kept closed and simply revealed its everyday side painted mostly in shades of grey it was only opened to display all of its golden glory on church feast days and festivals.

The central panel depicts the most important topics and most senior saints on the altarpiece. Thus the wings allowed religious images to be veiled and revealed in significant ways. The method of hinging together several panels, some painted on both sides, also allowed more space for depictions - such as the saints to whom the altar was dedicated, as well as for portraits of the donors who commissioned and paid for the altarpiece, so as to guarantee their souls a safe passage to Paradise.

Recent research has shown that right here in Cologne there were altarpieces that interacted with the rest of the altar's adornments: some retables are incomplete, both in form and content, without the altar cross that once stood in front.